Kenyan asylum seeker Delphina Ngigi arrived in Canada on Feb. 16 seeking asylum. The next night, she unsuccessfully sought shelter for six hours on one of that winter’s coldest nights before she was allowed to stay in a Mississauga shelter’s lobby. Three days after she arrived in Canada, she collapsed and died in hospital.

Ngigi’s tragic experience is partly why leaders in the African Canadian Collective (ACC), a network of Black-led non-profits, want the Black community to have its own homeless shelter, especially with the arrival of an historic number of newcomers last year. Statistical data from 2021 suggests 31 per cent of respondents in a city-wide homelessness assessment identified as Black, while Black individuals make up only 7.5 per cent of Toronto’s population.

They’re up against tough odds: a lack of resources, inexperience, and the City of Toronto’s inability to effectively address worst-case scenarios, having to build after disaster has already struck — including deaths like Ngigi’s and the current global migrant crisis.

The city currently owns a few shelters while partially funding independently run shelters. There are shelters for families, men, women, teenagers, the 2SLGBTQIA+ community and Indigenous community.

Telling our own stories.

Creating community-powered journalism that centres and celebrates Black, Indigenous and communities of colour in Canada.

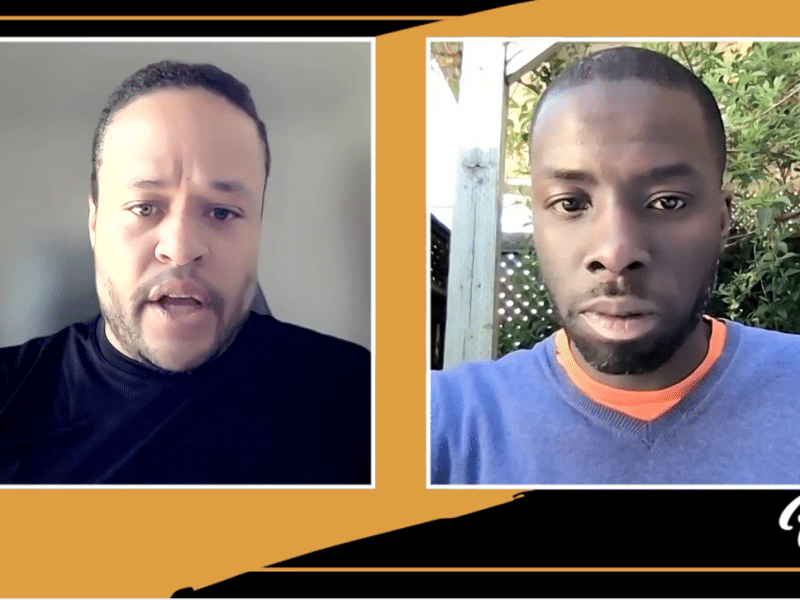

“When it comes to actually creating more cultural-relevant services, it’s now possible to be done in the general shelters,” says Kizito Musabimana who leads the Rwandan Canadian Healing Centre, one of the organizations in the ACC, and who credits a sense of community for saving his life.

A child during the the 1994 Rwandan genocide, his past caught up to him in 2007 in Toronto where he struggled with unrelenting thoughts of suicide. Finding a community of like-minded Black people in the Black Conscious movement, he eventually founded the RCHC in 2018 and is currently its executive director.

“I kind of had to make a decision to either do the deed or do something else,” says Musabimana.

When Ngigi died in early 2024, Musabimana decided again to act.

“That’s when I began intentionally bringing folks together for this particular file and then the city directed everybody who was saying, ‘we want to do our Black-run shelter’ — they were directing them to our collective,” says Musabimana.

Community leaders like Musabimana and the city’s Confronting Anti-Black Racism (CABR) unit hosted discussions around the city this summer to engage the community and inform CABR’s new 10-year action plan which will be finalized in January. They held a final meeting on Oct. 3 at City Hall to get public feedback on community interests.

While CABR’s renewal is considered by its staff as a success, Mayor Olivia Chow pushed for more progress and action, reflecting on the many plans that have “gathered dust” in the past.

In July 2015, police responded to a call about a disturbance in a shelter. Resident and asylum seeker Andrew Loku paced around in a winter jacket, holding a hammer. A normally kind man, Loku confronted a neighbour, entered their home and abruptly walked out. Then police arrived and Loku walked directly toward them with the hammer in hand. Out of frame of security footage, police shot him.

The police officer who killed Loku was acquitted, causing protests and sit-ins in front of police headquarters, led by Black Lives Matter Toronto. It ultimately led to the Confronting Anti-Black Racism (CABR) unit, tasked with dismantling institutionalized racism in the city. The retelling of Loku’s story by CABR staff usually comes with the same refrain: he was “before George Floyd.”

After Loku’s death in 2015, city hall adopted a broad motion on police reform that was created to attend to people dealing with mental health and addiction issues. Its work also covers shelters. Black people in the shelter system have long held grievances against it for anti-Black racism.

Meanwhile, the ACC held a press conference at the end of July to report on the status of Black refugees in the city on the anniversary of the newcomer crisis, when federal funding was cut and hundreds of newcomers were left sleeping on the streets.

Even among city staff, it is generally thought refugees will be prioritized among the needs for a Black-led shelter, but the ACC has to compete with more seasoned shelter service providers for the project bid. City staff seem keen to continue conversations with the ACC, but the outcome is not assured.

“Some days you think you’re getting somewhere, and some days you kind of think it’s not going to happen,” says Musabimana.

He wanted to partner with the city since ACC members include churches that led the response to the refugee crisis.

The executive director of the Pilgrim Feast Tabernacles, Nadine Miller, said her church first took in 40 refugees from Uganda in July 2023, which later turned into 80 people from 13 countries. She said they ordered beds, borrowed credit cards, rented office space for sleeping and took profits from their restaurant and subsequently shut it down to use the kitchen facilities for refugees.

“I don’t think the cities are strong enough to bolster the weight of the influx of refugees,” says Miller.

Toronto leased thousands of hotel spaces during the pandemic, costing $253 per person a night, a move it conceded was reactive. The city is now working to create long-term structures that don’t bleed funds.

It secured federal funding this year to create refugee shelters, as 4,063 of its short-term leases end this year. The Black-led shelter will be funded through its Homelessness Services Capital Infrastructure Strategy. The city has budgeted for 20 new shelters, with one for Black communities, each housing between 80-100 individuals.

Toronto is trying to address an overwhelming global migration trend, stemming the tide of a tsunami with an assortment of buckets. The UN predicted forced displacements will exceed 120 million people this year.

Musabimana wants more humane care as a focal point for Black-led shelters because of all he’s experienced in this lifetime. He thinks there will always be wars.

Despite this, he hasn’t given up. The Rwandan War did end, and he came out of his PTSD with purpose, hoping for better outcomes for others than he had.

“The universe does weird things where it’s like, you think this happened to you and you didn’t deserve it. But yet, here you are doing the things that you’ve always wanted to do as a child before the genocide, before any of these traumas,” he says.

We’re counting on readers like you

The Resolve creates community-powered independent journalism centring and celebrating Black, Indigenous and communities of colour in Canada. If you think this work is important, join us and become a founding member of The Resolve.